The long-term seemingly linear graphs of the stock market might make you think it works like an escalator – on its way up. But in reality, between those 2 end dates of your graph, markets may have oscillated between extremes for several years before eventually delivering long term compounded returns.

Even though the market or stock prices are theoretically said to be a slave to earnings, they never trade at ideal valuations based on the earnings. Rather, they always oscillate between phases of over valuations and under valuations.

There are three powerful forces that drive this kind of oscillation and the eventual returns. They are:

- Market Liquidity

- Cycles

- Human behaviour

By comprehending these dynamics, investors can enhance their long-term returns.

A key advantage of understanding these forces lies in capitalizing on market fluctuations. By anticipating and responding to swings in the overall market and specific sectors, driven by these factors, investors can potentially optimize their portfolio performance over time.

Here is a detailed discussion about these 3 powerful forces that drives stock prices or stock markets or broadly equities as an asset class.

This article is divided into 3 parts as each of these parts require detailed discussion.

Liquidity

Consider these instances:

- Vodafone Idea’s FPO was oversubscribed six times by institutional investors.

- The Nifty index is tantalizingly close to 25,000 despite relentless selling by foreign investors.

- India boasted 100 unicorns in 2022.

- Private equity firms are celebrating lucrative exits.

- And multinational giants like Whirlpool, Timken, and Hyundai are raising substantial funds by valuing their Indian subsidiaries higher than their parent companies could in their home markets.

These are all testaments to the immense power of liquidity. Liquidity is the lifeblood of any market.

So, what is liquidity and how does it influence market and investors? Let us discuss.

What is liquidity?

Liquidity is nothing but the total quantum of money flowing into or out of the market or an asset class.

While domestic liquidity is the savings of domestic investors – either directly or through institutions, overseas liquidity is the dollar money that is chasing asset classes in the form of foreign institutional investments.

It is channelised into markets through mutual funds, Alternate Investment Funds, Portfolio Management, Private Equity, etc.

This money chases different opportunities at different times. Imagine a time, just 3 years ago in the aftermath of Covid, when banks were flush with money and their Current and Savings Account (CASA) ratio climbed to as high as 50% and above. Today, banks are struggling to raise deposits while the CASA ratio has been falling continuously.

Clearly, the money that took shelter in banks at the time of uncertainty is now chasing risk assets, creating huge amount of liquidity in risk assets.

In the case of dollar money, whenever interest rates fall in US, money moves to risky assets across the globe (i.e the FII inflows) and vice versa. This has been a major source of liquidity for markets world over, for a long time.

What liquidity does

- Too much money chasing too few stocks: Liquidity is undeniably essential for markets to function efficiently and accurately price assets. However, an overabundance of liquidity can fuel irrational exuberance. It pushes up the valuations as too much money starts chasing too few things and then it creates a cycle of exiting high and trying to enter whatever is left over with lower valuations. For example, if you exit a stock at 50 or 60 PE in a bull market, you will be happy to buy something else trading at 30 or 35 PE irrespective of the quality of the business or its financials.

This is how a broad-based rally takes shape in stocks irrespective of their fundamentals. And sometimes this liquidity has a spill-over effect in other asset classes.

We have also seen significant spill-over effect of favourable stock market valuations into the urban luxury real estate demand as well. Anecdotal evidence of India’s rich promoters, whether from start-ups or otherwise, buying luxury apartments, suggests this.

- A seller’s market: Liquidity makes the market more attractive for sellers or issuer of shares (PE Players, Promoters, IPO) than buyers. Imagine the late 2021 IPO boom where companies such as Paytm, Zomato, Nykaa, PB Fintech, etc drove a mammoth fund-raising amounting to $5 billion in quick succession. Domestic investors are yet to make meaningful return in most of these stocks, 3 years after IPO. PE and MNC Promoters also caught up to these mouth-watering valuations. Private Equity Blackstone mopped up Rs.15,000 crore through primary (IPO) and secondary sale of its shares of auto parts maker Sona BLW by selling its 67% stake in the Company. This with a business that had a revenue of less than Rs.3,000 crores and profit less than Rs.500 crore. PEs such as Barrings and Blackstone again pressed the button to take major exits in IT stocks such as Mphasis and Coforge (formerly NIIT Tech) totalling close to $1 billion each.

We also saw Whirlpool, Timken, BAT, etc deciding to take money off their Indian subsidiary by selling their stake in the secondary market as they were being forced by their shareholders to monetise their stakes for corporate purposes at home.

- Bubbles and the burst thereafter: While Liquidity is the key driving force behind every asset class, what excess liquidity does is irrational exuberance and eventual bubble.

Even as the Japanese stock market Index Nikkei may be hitting new high after 30 Years, it still stands out as the greatest example of the biggest liquidity driven bubble in 1989 (popularly called the Nikkei Bubble) when the Market Cap of Japanese stock market was 45% of Global M Cap!

A tiny country’s market cap ruling the world for whatever narrative was at play at that point of time and the spill-over effect of that liquidity driven asset bubble lasted for 3 decades with deflation haunting the Japanese economy.

The unprecedented surge of PetroChina’s market capitalization by over 100% on its 2007 listing day was a stark illustration of the power of liquidity over fundamentals. Initially dwarfed by industry titan Exxon Mobil, PetroChina’s valuation astoundingly doubled within a single trading session, a feat impossible to attribute to earnings alone. This extreme market behaviour highlighted the distortive effects of excessive liquidity on asset pricing.”

Let’s take the case of India. While the 2003-2007 period offered a precursor, with dollar inflows inflating asset prices in BRICS nations, the subsequent global financial crisis underscored the dangers of excessive liquidity. Many emerging economies, including India, struggled to absorb the influx of capital without destabilizing effects. This apart, The Indian market is used to pockets of irrational exuberance in every bull market starting from the tech bubble in 2001 to infrastructure and real estate boom in 2007 to the small cap gold rush of 2017 and the quality stocks mania prior to Covid.

India’s present situation: Now, India’s market capitalization-to-GDP ratio (read more about the market cap to GDP ratio in this article: Is the Buffett indicator the right indicator for stock market valuation?) has surged to over 140%, yet a full-blown liquidity-driven bubble hasn’t transpired. But who knows, if India were to be considered as a separate asset class by global investors in the emerging economic and geopolitical scenario, one cannot rule out huge global liquidity chasing India at some point of time. This can eventually lead to a bubble (like it happened with Japan). We are not suggesting this is the case but just a conjecture 😊. (I borrowed this from veteran investor Manish Chokhani. You can listen to him here).

For value conscious investors, such an abundance of liquidity makes life extremely difficult. And it creates self-doubt as to whether they are missing something or doing something terribly wrong. It creates FOMO and force investors to embrace irrationality.

When liquidity dries up

The most painful period comes when liquidity completely goes away.

As Warren Buffett said, “Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked.”

We have seen this happen in the 2008 Global financial crisis and before that during Tech bubble as well.

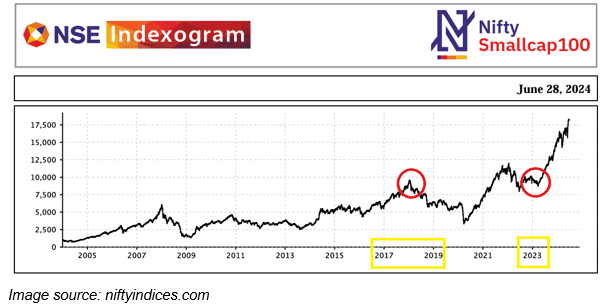

A classic case of liquidity withdrawal causing massive damage locally was the smallcap boom in 2017 after SEBI’s new classification of MF schemes and classification of stocks based on M Cap for MF schemes to buy. It washed away liquidity completely that the Small cap index saw new high six years later only in 2023.

India’s present situation: At present, the Indian market has been fortunate to be saved by domestic liquidity – in the form of DII and SIP inflows. This despite the reversal of dollar liquidity in the last 3 years, with US FED raising rates from 0-5%. However, any domestic outcome that cause panic among domestic investors can reverse this domestic liquidity as well.

Summary

Liquidity is a market behemoth. It can inflate bubbles to absurd heights, seduce investors with irrationality, and inflict severe damage on retreat. Rationality is the only armour against its wild swings.

Cycles

Cycles – economic, sector or earnings – is another powerful force that drives markets. What exactly do we mean by cycles here? Changes in the economy, sector or earnings of companies characterised by expansion, peak, contraction and trough is typically called cycles.

#1 Economic cycle

The spill-over effect of capex and real estate boom resulted in banking crisis between 2013 and 2019. This took significant government and tax-payer’s resources to steer the economy back.

But today, with well capitalised banks and under leveraged corporate balance sheets, a different cycle is taking shape, a growth cycle with 7%+ GDP growth Vs a contraction cycle from 8% GDP growth to 5% prior to Covid.

An expansionary cycle is always accompanied by a greater number of companies doing well, eventually leading to a broad-based market rally. Thankfully, this time around, we are further supported by a global expansionary cycle (in areas like manufacturing, energy transition, etc), enhancing prospects of goods exporters.

All this is reflected in corporate profit to GDP ratio inching higher towards 4.8% to a 15-year high in FY24, closer to levels what we have seen in 2007 with cyclical sectors including autos, industrials, financials and public sector enterprises (energy, resources and defence) pushing up the corporate earnings cycle.

Check:

- India: corporate profits to GDP ratio by Nifty-500 2023 | Statista

- Rising Corporate Profitability bodes well for India’s Growth Story! (hdfcfund.com)

Going by the data from our Stock Screener, the top 100 manufacturing companies by M Cap from manufacturing sectors like auto ancillaries, engineering & capital goods and electrical goods have grown their revenues, EBIDTA and PAT by 25%, 36% and 50% respectively in the last 3 years. These companies have generated absolute profit of Rs.45,000 crore in FY2024 with their combined M Cap touching Rs 30 lakh crore.

If we add the profits of top automobile OEMs as well, then the total PAT from these manufacturing sectors would touch Rs.1,00,000 crores in FY24.Economic cycle, business cycle and valuation cycle are playing in tandem for these sectors.

#2 Earnings cycle

Let’s start with Nifty’s earnings over the last 5 years. After Nifty’s record beating rally of 3.5X post Covid (2X from pre-Covid), the price earnings (PE) ratio is still same as pre-Covid which in turn means the rally is supported by earnings growth – or expanding earnings. This is a classic case of earnings expansion driven upcycle. In other words, the PE did not move up despite up move in the numerator(price) as the denominator (earnings) kept pace.

In fact, FY24 turned out to the first year in a decade where Nifty earnings growth was at or ahead of expectations.

So, what led to this phenomenal earnings growth despite the challenges due to Covid? Here’s a quick glimpse into the Nifty companies that delivered mind boggling earnings growth.

A third of Nifty companies have nearly quadrupled their earnings in the last 4 years as you can see. It is because of them that the market valuations are not expensive as of today.

These are not basket of stocks or sectors that investors were generally interested in prior to Covid. In fact, they were ignored stocks as investors’ affinity towards predictable earnings stocks, labelled as “quality stocks”, were at the peak prior to Covid.

# 3 Cycles driven by other factors

Sector cycles from consolidation: Some cycles can be deceptive because they may not be cycles related to the normal moves of a sector. Ever wondered how many of us missed the PSU bank rally? These kind of upcycles can be picked by being attentive to everything that matters in the sector - NPA, losses, scams, politics, quality of management and so on. There was a trough and an up move but then unless one noticed every change, it would likely have been missed.

Just to illustrate, here is how the cycle has played out on in the PSU bank space:

- The cyclical downturn eventually led to consolidation that every surviving PSU bank has many other banks inside it, pursuant to mega merger

- Because the merger increased their size significantly, each PSUs bank’s share price today is the sum of many.

- With asset quality issues abating and new lending cycle picking up, the net positive impact of size on the income and in turn net profit became significant.

- In a sector where money itself is the raw material (deposits), PSU banks did not have a problem with deposit mobilisation. When veteran investor late. Rakesh Jhunjhunwala called bottom for PSU banks in 2019, he said two things 1) provisions have peaked and 2) banks that can raise deposits will do well. This wisdom came at the bottom of the cycle for banks 😊

- Consolidation became the deal-clincher for this sector. Had PSU banks been simply allowed to survive through individual recapitalisation, this would NOT have been the outcome, resulting in a bunch of “Zombie Companies” (banks). Instead, consolidation allowed surviving ones to comeback stronger in the new cycle, thanks to the government pushing for it at the right time.

It is the same consolidation story with metals, cement, real estate, etc. Each company has many more companies inside it, which they acquired at far below their replacement cost from NCLT before the turn of an upcycle.

When Ultratech acquired 6 cement plants (21 million tonnes) of JP Associates at one go, there was no other company that could fund such an acquisition amid the banking crisis. And the forceful selling of assets, leading to a lucrative deal for Ultratech.

Same followed through with Steel sector as well, be it Tata Steel’s acquisition of Bhushan Steel or JSW’s acquisition of Bhushan Power and Steel. Their earnings today are on a far higher capacity than in the previous cycle, thanks to global cycle turning in their favour.

The PSU financier, PFC, that you see today owns 52% of REC as well, which makes PFC’s consolidated AUM and profitability look mammoth. This was not the case in the previous cycle.

By virtue of their bigger size through acquisitions and consolidation, the earnings potential of such companies in the new cycle becomes far higher than in the previous cycle. And that is when stock prices start responding – with a move up north. And the consolidated size makes them still inexpensive.

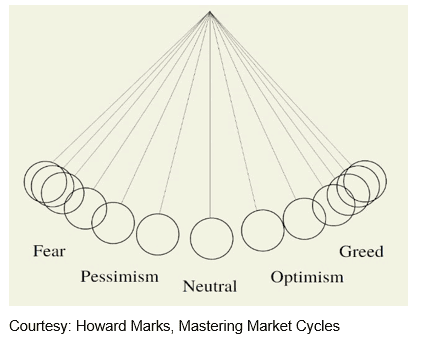

This is what Howard Mark, veteran investor and the author of the book “Mastering market cycles” means by saying; “Cycle regenerate itself”.

To sum up…

After a boom cycle, the decline happens, inevitably, when many companies go out of business or go bankrupt or find shelter in bigger ones. The consolidation, through acquisitions, at the bottom of cycles always happen at far cheaper valuation for assets and turn out to be value accretive for surviving companies. The surviving ones emerge stronger and lead the next cycle.

Geopolitics triggered cycles: There are some “odd” cycles also playing out, like the one in defence. The world moving from peace to war is leading to mammoth multiple expansion for defence players, which would not have happened otherwise. (Even we overlooked this factor😊 giving due weight to management, order book, earnings growth, PSU tag, PE multiples etc while we advised early profit booking in the only private defence stock that we recommended).

While this leads to irrationality in valuations, nobody knew where they could stop. Obviously, their ability to hold high multiple may be tied to how long the periods of conflict last.

As Yuval Noah Harari, a well-known historian and the author of the book “Sapiens” pointed out, in the last 30 years more people died of diseases due to eating than due to conflicts. The world was going through a long phase of peace in its history. Peace and globalisation are two sides of the same coin that a reversal may have far reaching consequences for different economies. For example, the stock market of countries in conflict zones can trade at permanent discount while this may not affect those in non-conflict zones.

Summary

There is no better book than Howard Marks “Mastering market cycles” to understand cycles and their interrelationship. Here are our takeaways from it:

Interrelationships Among the Cycles

- Economic cycle drives business cycle: A strong economy typically leads to increased corporate profits and stock prices. Conversely, an economic downturn can negatively impact businesses and the market.

- Business cycle impacts market cycle: The performance of companies directly influences market returns. Strong corporate earnings often lead to market rallies, while poor earnings can trigger declines.

- Market cycle influences valuation cycle: During market booms, asset valuations tend to become inflated as investors become overly optimistic. Conversely, market downturns often lead to depressed valuations.

- Valuation cycle feeds back into market cycle: Overvalued assets are susceptible to price declines, which can contribute to market corrections. Undervalued assets, on the other hand, can offer attractive investment opportunities and fuel market rallies.

Understanding these interconnected cycles is crucial for successful investing. By recognizing where we are in each cycle, investors can make more informed decisions about asset allocation and risk management.

Human behaviour

Investor behaviour plays a significant role in market cycles. Greed, fear, and herd mentality can lead to irrational decisions. Understanding these psychological factors can help investors make better choices.

Let us begin with risk aversion in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The focus then turned to “quality stocks” - be it foreign institutions or domestic institutions or the investment managers like PMS and AIFs. What was visible was ‘herd mentality’ or ‘bandwagon effect’.

Common behavioral biases

Bandwagon effect: It is a psychological phenomenon in which people do something primarily because other people are doing it, regardless of their own beliefs.

Confirmation bias: It is the tendency of people to favor or accept information that confirms or strengthens their beliefs or values and is difficult to dislodge once affirmed.

Recency bias: It is a cognitive bias that favors recent events over historic ones; a memory bias (due to our short memories). Recency bias gives "greater importance to the most recent event".

Loss Aversion: Loss aversion is a cognitive bias that suggests that for individuals the pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining, which prevents them from booking losses even after realising that they took a wrong decision.

Sunk cost fallacy: The sunk cost fallacy is our tendency to continue with something we’ve invested money, effort, or time into—even if the current costs outweigh the benefits, leading to even averaging of stocks with no prospects.

Price anchoring: Here, investor relies heavily on the anchor to determine whether or not a particular investment is a good choice for their investment portfolio. If a stock that has been going up for years falls 20%, an investor would be tempted to buy it, keeping its high price as the anchor.

Mental accounting: Mental Accounting is a cognitive bias that states the tendency to treat one's money differently based on factors such as its intended use or its source.

Regret aversion: This bias seeks to avoid the emotional pain of “regret” associated with poor or sub-optimal decision making.

With quality stocks performing well in the market over time, “recency bias” set in. Investors believed that only this basket can deliver returns and not anything else. That led to concentration of capital in the quality basket, pushing up their valuations.

The rest were labelled as bad businesses or bad companies or bad management.

While this was happening, there was also new-found fancy in the market for e-commerce and digital players. Foreign inflows gravitated to this space, riding on the global narrative with huge concentration of capital in those pockets. Needless to say, local PE money followed suite – the herd mentality kicking in, amidst promising narratives.

This led to the birth of 100 Unicorns in India by 2022 (we need to count how the number stacks up today after the Byjus and Paytm episodes 😊).

Meanwhile, this bias towards quality stocks further accelerated in the aftermath of Covid (due to risk aversion) until the realisation happened that the bulls may have migrated long ago to other pastures.

So, what were the market participants ignoring? One, the valuation excesses created due to concentration of capital in other pockets. And two, commodity related sectors such as materials, energy, real estate, etc. That was leaving a huge valuation gap in the ignored sectors.

If it was ‘recency bias” that was driving market participants’ attention towards “quality stocks”, “risk aversion” was keeping investors away from resources, materials, energy and real estate stocks.

The narratives with respect to clean energy transition (from traditional fuel), black money, bankruptcies, regulations, etc were also pushing investors away from those businesses. Investors were finding little reason or evidence to bet on those businesses.

But in all this herd behaviour, was there no evidence of the potential in the sectors that investors kept away from? Not really. There was evidence. The evidence was ignored.

There was consolidation, debt reduction, etc happening where surviving companies were becoming larger and stronger.

But decision making in such stages can only be made by investors who are closely attentive to cycles as explained in the previous session. Not an easy thing to stray from the herd!

Often, labels like 'great business,' 'stellar management,' and 'high moat' are retrospectively applied to stocks after they have enjoyed significant price appreciation. This post-hoc attribution reinforces investors' beliefs, a phenomenon known in behavioural finance as confirmation bias.

As a result, a stock's market value is not solely determined by its intrinsic earnings potential. Instead, it is a composite of its fundamental worth and market sentiment, the latter being significantly influenced by behavioural biases.

During market frenzies, sentiment can account for as much as half of a stock or sector's valuation. As Howard Marks noted in 'Mastering the Market Cycle,' valuations oscillate like a pendulum, swinging wildly from euphoria to despair.

At either extreme of the pendulum, it is not earnings or the value of assets that decides a stock’s market price, rather it is a sum of quantitative and behavioural factors. And the “sentiment” is the sum of many behavioural biases.

What we see today: What we are seeing now is the opposite of risk aversion and the pendulum is swinging to the other extreme.

Investor euphoria, fuelled by stock market gains, often leads to a willingness to deploy funds into increasingly overvalued assets. This behaviour is exacerbated by mental accounting, a cognitive bias that segregates money into mental buckets. Profits are often viewed as 'play money,' less sacred than initial investments or retirement savings. As a result, investors become more tolerant of risk and less discerning in their stock selection.

Meanwhile, there are also other behavioural biases like “loss aversion”, “sunk cost fallacy” and “anchoring” that pushes investors to do costly mistakes. These play out in the minds of both retail, institutional investors and fund managers alike and collectively lead to irrational decisions. Institutional investors and fund managers may have an edge in attempting to get rid of these biases with well-laid out processes and strategies, compared to individual investors.

Summary

By understanding and anticipating these behavioural patterns, investors can position themselves to benefit from market cycles. Howard Marks encourages investors to do the following to get over these biases:

- Second-level thinking: He encourages investors to look beyond obvious factors and consider less apparent implications.

- The importance of discipline: Maintaining discipline in the face of market fluctuations is essential, according to Marks.

Here are a set of few books that may be useful in riding over the behavioural biases.

- Value investing and behavioural finance by Parag Parikh

- Why smart people make big money mistakes by Gary Belsky & Thomas Gilovich

- The Halo Effect by Phil Rosenzweig that discusses business delusions that deceive money managers.

- The Invisible Gorilla by Christopher Chabris & Daniel Simons that discusses how our intuitions deceive us.

- Thinking fast and slow by Nobel Laurette Daniel Kahneman

- Finally, Thinking in Bets & When to Quit by renowned poker player Annie Duke

14 thoughts on “The 3 forces that make or break the market”

Excellent article and put across in an easy understandable language.

Thank you sir

A well researched, exhaustive article Mr Chandrachoodamani. Wonderful read.

Thank you sir

Wonderful article..

Thank you sir

Well captured.

Behavioural biases – sometimes are known only in hind-sight. Partly because there are times in the past you would have seen something flatter to deceive. You will think you could buy into a PSB. You will see a government come in and make them do something weird. Even this round, if you notice there was (in hindsight) a close shave for the current government to come back. If it had flipped who knows how this PSB story would have played out. So sometimes behavioural biases are based on interpretation of possibilities…

————-

You refered to the following info:

India: corporate profits to GDP ratio by Nifty-500 2023 | Statista

Unfortunately it appears to be behind a pay-wall.

Any ability to throw some more details about the trend on this…

Yes, absolutely sir

Sorry to know that the link is behind a pay-wall. It is just a graphical representation of how much was corporate profit as a % of GDP has moved over the last 25 years. The ratio peaked at 5.1% or so in 2007 and now we are back at 4.8% after hitting close to 3% levels during 2017-18-19 years (bank provisions also peaked out in FY19).

The HDFC AMC article link given there also contains same graphical info. Placing the link here for your reference

https://www.hdfcfund.com/knowledge-stack/deep-dives/tuesdays-talking-points/rising-corporate-profitability-bodes-well-indias-growth-story

Thank you

Very useful article. Well written.

Thank you sir

Great article. Thanks!

Thank you sir

Oh my God. Could not believe how the learning of multiple cycles can be put to a precise 15 to 20 mins patience read. Kudos.

Thank you sir

Comments are closed.