![]() Commodity prices have been rallying globally in the last few weeks, with some folks speculating if this is the start of a new commodity ‘super-cycle’. With all eyes on commodity stocks, the sweetest of them all, sugar industry companies, too have been trending higher. Leading players such as Balrampur Chini Mills Limited, Dhampur Sugar Mills Limited and EID Parry saw their stocks hit 52-week highs in June (Balrampur Chini Mills Limited and Dhampur Sugar Mills Limited even hit all-time highs) and some stock prices even doubled in the last six months. Here we take a look at the sugar sector in India and its nuances.

Commodity prices have been rallying globally in the last few weeks, with some folks speculating if this is the start of a new commodity ‘super-cycle’. With all eyes on commodity stocks, the sweetest of them all, sugar industry companies, too have been trending higher. Leading players such as Balrampur Chini Mills Limited, Dhampur Sugar Mills Limited and EID Parry saw their stocks hit 52-week highs in June (Balrampur Chini Mills Limited and Dhampur Sugar Mills Limited even hit all-time highs) and some stock prices even doubled in the last six months. Here we take a look at the sugar sector in India and its nuances.

An overview

India is the largest sugar consuming country in the world and the second largest sugar manufacturer excluding traditional sweeteners such as gur/khandsari. The sector has the reputation of being plagued by cyclicality and has gone through varying degrees and forms of control by the Government. Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka lead in terms of sugar production with U.P. having more private mills and Maharashtra having more under the cooperative model.

Production process

The sugarcane crop needs a lot of water and therefore, in peninsular India it is monsoon dependent while in States like UP, it relies on water from the perennial rivers. Sugar mills in India source their sugarcane from a ‘command area’ which is statutorily allocated to them. The price for sugarcane procurement is also regulated, with the Central government fixing a ‘fair’ price each year. State governments sometimes fix their own prices over and above this.

After harvest, the perishable sugarcane is transported to the concerned mill where it is prepared and crushed and the juice is extracted. The residual fiber left behind at the end of the crushing process is called bagasse and is used to generate steam and electricity (cogeneration) which is used by the mill. Excess power generated is sold to the grid. The extracted juice is boiled and the sugar is extracted from the same in three stages. The residue left at the end of this process is called C-heavy molasses. At this point, no more sugar can be extracted and the extracted sugar is further processed and cleaned to make it ready for consumption. The C-heavy molasses is used in the manufacture of alcohol, yeast and cattle feed. This alcohol is used to produce ethanol. However, ethanol can also be directly produced from cane juice (sacrificing all the sugar output) or from B-heavy molasses which are the residue after the cane juice is boiled and sugar is extracted twice (sacrificing not all, but some of the sugar output). Naturally, the yield of ethanol is highest when directly produced from cane juice, followed by B-heavy molasses and least when produced from C-heavy molasses. Integrated sugar manufacturers have a more broad-based revenue source, and are able to generate revenue from not only sugar but also cogeneration and ethanol production compared to standalone sugar mills.

Cyclicality

Although the sugarcane crop is a lucrative cash crop with farmers statutorily assured of a minimum price from the mills, the sugar sector is subject to considerable cyclicality and has the reputation of being tumultuous. A few years of rising production resulting in record sugar production, often leads to a build-up of inventories and a crash in sugar prices as the market faces a supply glut. Sugar mills, given that they have to procure cane at fixed prices from farmers irrespective of end-product realizations, delay their payments for cane. This in turn leads to build up of the notorious cane arrears to farmers, even though mills are liable to pay farmers within 14 days. High arrears lead to lower cane plantings the next season, as farmers switch to better alternatives. Sometimes poor monsoons or pest attacks also curtail production. When this curtails output, balances out demand and supply, and props up sugar prices, the next upcycle begins. This sugar cycle in India traditionally followed a five-year pattern with three bumper years followed by two deficit ones. In recent years though, with farmers consistently preferring sugarcane (both sugarcane procurement and prices are assured by the sugar industry whereas for crops such as foodgrains, procurement by government agencies at MSP is uncertain), the sugar industry has faced more glut years with poor prices, than deficit ones with lucrative realizations.

Highly Regulated

In an effort to shield farmers from this cyclicality and to address the issue of cane arrears, the Government deploys several measures that result in the industry being subject to a high degree of regulation on every aspect of its operations.

#1 FRP / SAP of cane :

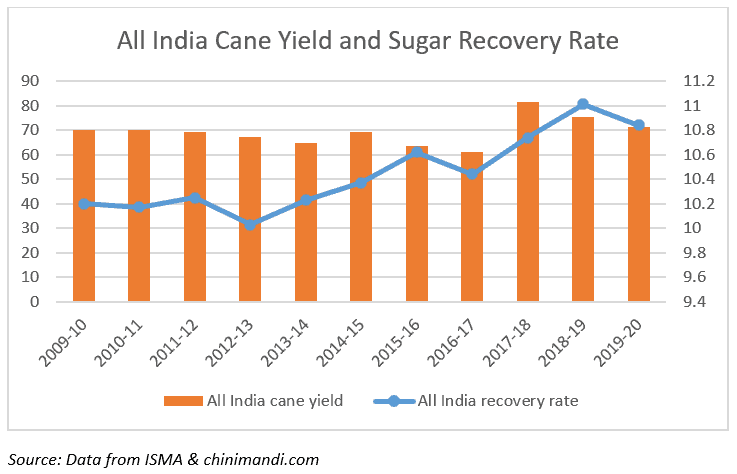

The minimum price at which sugarcane has to be bought by the mills from the farmers every year is fixed by the central Government and is known as the Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP). The FRP, which is currently Rs. 285 per quintal for 2020-21 sugar season assumes a minimum recovery rate (amount of sugar recovered after processing a definite weight of sugar cane) of 10% and provides for a premium of Rs. 2.85 per quintal for every 0.1% increase in recovery rate. In addition to the FRP, some states such as UP declare a State Advisory Price (SAP) for sugarcane which is usually higher than the FRP. For e.g. the SAP in UP, which has remained the same since sugar season 2017-18, stands at Rs. 315 per quintal for the common variety, Rs. 325 per quintal for the early variety and Rs. 310 for the rejected variety. The minimum price of cane is fixed with a view to cover the costs and assure a margin to the sugarcane farmers but is not linked to the price of sugar and therefore, often ends up squeezing the profitability of sugar manufacturers. Further, the assurance of receiving a minimum price for their produce, has encouraged farmers to grow more cane, even in a scenario where there is a surplus, placing more demands on limited water and land resources. The report of the Task Force on Sugarcane and Sugar Industry, March 2020 recommends ways to incentivize farmers to diversify in favour of less water-intensive crops.

#2 MSP of sugar :

Many of the woes of the sugar sector can be attributed to sugar prices which used to be market driven but in 2018 a Minimum Selling Price (MSP) for sugar was introduced, setting the floor at the factory gate for the domestic market. This was done to ensure that the mills cover at least their cost of production during an industry down-cycle and thereby are able to pay farmers their cane dues which had once again reached worrying levels due to depressed prices just before the introduction of MSP in June 2018. Currently, the MSP of sugar stands at Rs. 3,100 per quintal. How well this MSP works in practice is however yet to be tested across the cycle. With 2020-21 tending to be another surplus year, it is already showing signs of strain, with some mills resorting to selling their inventory at below the MSP just to be able to clear their cane dues, prompting the Central Government to issue a notification asking for adherence to the MSP and quota. Concerns have also been raised that despite being increased from Rs. 2,900 per quintal in 2019, the MSP still does not cover the cost of manufacture mainly due to high cane prices. Indian Sugar Mills Association (ISMA) has already raised concerns over depressed ex-mill prices causing some mills to export under OGL without any export subsidies, just to be able to generate some liquidity.

While the domestic wholesale price of sugar has mostly remained range-bound, it does not reflect the distressed sales being made below the MSP indicating that had it not been for the MSP, the selling price of sugar could go lower.

#3 Selling quota and Buffer stock :

Earlier sugar mills could not release their output in the market in full with the government ‘levying’ a portion of each mill’s output for distribution through the PDS system. Quotas between this ‘levy’ portion and ‘free sale’ portions used to be fixed, forcing mills to sell a portion of their output at a discount. This levy- free quota system has since been dismantled. However, the amount of sugar that mills may sell in the market every month is determined through a release order. This system however continues. Additionally, the Government uses tools such as stock holding limits under the Essential Commodities Act, buffer stock, export curbs etc. from time to time to tackle over-supply or curb shortages in the market that can hurt consumers.

#4 Export quota and subsidy :

The export of sugar was highly regulated in the past through the requirement of release orders and customs duty, but these have given way to newer forms of control now. Currently, to address the oversupply in the market, the Government sets a Maximum Admissible Export Quantity allocated to sugar mills for each sugar season. This is supported by an export subsidy for exports up to the MAEQ allocated to individual sugar mills, which is expected to cover costs and make exports more viable.

Current status

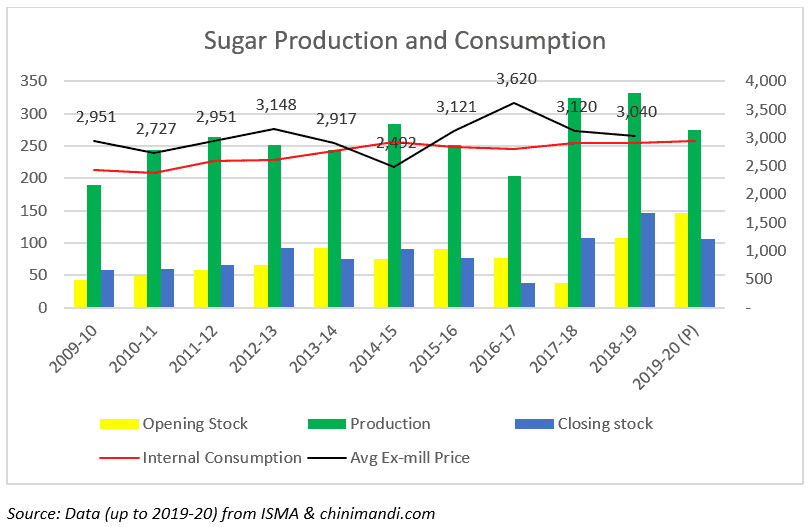

Owing to consistently high production in the last few years, (especially in 2017-18 and 2018-19 which saw record highs), improved recovery rates and cane yields, the sugar year 2019-20 (October to September) began with a record high opening stock of 146 lakh tonnes. The year closed with 106 lakh tonnes thanks mainly to lower production owing to a below-normal rainfall which turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

The Current year : 2020-21

The current sugar year that began on October 2020 has already seen higher production than the previous year. Production until May 31, 2021 stood at 306 lakh tonnes as against only 270 lakh tonnes at the same time the previous year with almost all the states (especially Maharashtra and Karnataka) posting an increase except UP. This increase has been attributed to an earlier start of crushing in Maharashtra, greater availability of sugarcane and unhindered activity through the Covid second wave as sugar is an essential commodity.

Sugar mills also saw some extra cane being diverted to them, as gur and khandsari units remained closed due to lockdowns. With domestic consumption not likely to see any dramatic jumps, concerns of oversupply have thus re-emerged. Though this could dampen prices, a crisis is unlikely as carry forward stocks are still moderate. Assuming domestic consumption stays flat at 260 lakh tonnes and exports are capped at 60 lakh tonnes, with production up to May 31, 2021, we could close in September with a stock of around 90 lakh tonnes. This is lower than the previous year, thanks in part to diversion of sugar toward ethanol production.

Next year : 2021-22

While official estimates on sugarcane acreage for the year 2021-22 are not yet available, buoyed by encouraging rainfall, farmers are estimated to have planted more sugarcane than the previous year. But it is also expected that there will be a greater diversion toward ethanol production in 2021-22, which could ease concerns of over-supply and a large closing stock.

Global markets and their influence

The sugar sector in India, though protected by a floor price in the form of the MSP, and numerous other measures as detailed above, is impacted by various factors reaching far beyond domestic demand-supply and regulatory factors.

Brazil, the largest producer and exporter of sugar (36% of sugar exports in 2019-20 according the World Bank Report - Commodity Markets Outlook April 2021), has a mature ethanol blending programme with a 27% blending at present and a large percentage of flex-fuel vehicles that allow the consumer to switch between ethanol or gasoline depending on the price after factoring in the lower mileage offered by ethanol. Further, ethanol prices in Brazil are linked to gasoline prices which are in turn linked to the international crude price. This means that mills can choose between producing sugar or ethanol depending on which one is more profitable. Brazil, as the largest producer and exporter of sugar in the world has the power to move both global supply and prices.

Recently, concerns have emerged on a possible global shortage. Brazil could see more cane diverted to ethanol production fueled by surging ethanol prices. Low yield of sugarcane due to drought could exacerbate the situation. Thailand, the second largest exporter of sugar is witnessing a bad crop. With rising global demand especially from China, global sugar prices have seen an uptick prompting the Government to cut back on export subsidies in India on May 21, 2021 from Rs. 6,000 per tonne to Rs. 4,000 per tonne. With sugar production in 2021-22 expected to be higher than the current year in India, exports could present an opportunity for the Indian sugar sector to offload its surplus. World sugar prices have recovered after the pandemic first hit in 2020 and have remained strong, buoyed up on concerns of shortage. However, what comes in the way of tapping into the export opportunity is the higher cost of production of sugar in India compared to other countries. Exports become attractive only with subsidies from the Government.

Some countries have raised concerns with the WTO, objecting to most of the measures by the Government of India especially export subsidies, claiming that they are in violation of WTO norms. India maintains that it is not in violation and is within its rights as a developing nation to do the above until 2023. But the jury is out on how much longer the Government can use these measures to cushion farmers from cane price dips and the sugar sector from cyclicality.

Ethanol Blended Petrol programme (EBP): Will it work?

While the Indian sugar sector lives through its usual swings in fortunes, one recent policy change that has fired up sugar stocks is the government demonstrating serious intent on the ethanol blending programme. With questions surrounding the current regulatory controls indefinitely to manage demand and supply in the sugar sector, the National Policy on Biofuels 2018 and the Ethanol Blended Petrol Programme under it offer some hope that the Indian sugar sector may have finally found a way to break out of its cyclicality. Approved in 2018, some of the key measures announced were:

#1 Clearly identifying various types of biofuels as 1G, 2G and 3G : 1G biofuels or conventional biofuels are made from sugar, starch, foodgrains etc. which are all food products. The technology for making biofuel out of these is quite mature (fermentation) and is being used by the sugar mills. While it addresses the issue of surplus, as in the case of sugar industry, and also wastage like in the case of damaged foodgrains, it also faces criticism in the form of food vs. fuel debates and also because it puts pressure on already strained land and water resources.

2G biofuels use non-edible feedstock such as non-edible oilseeds, used cooking oil, non-edible portion of crops such as straw, stalk and husk. The technology for this is not yet mature and not as widely used as that used in 1G biofuels. Despite offering advantages like converting agricultural waste into fuel, the initial capital expenditure for 2G plants can be prohibitive. 3G & 4G biofuels use algae, municipal solid waste and industrial waste to produce biofuels. Here too, technology is not yet mature is in need of more research and investment. Classification in the National Policy on Biofuels has been done with the objective of providing a focus on and incentives for advanced biofuels (2G and upwards) with a view to address the criticisms faced by 1G biofuels and to ramp up availability of biofuels.

#2 Expansion of the scope of raw materials allowed for ethanol production by allowing use of sugarcane juice and B-heavy molasses and other feedstock (grains such as rice and maize, feedstock). Conventionally, integrated sugar mills were only using C-heavy molasses for ethanol production. Use of B-heavy molasses and cane juice can improve ethanol yield while absorbing a higher portion of the sugar output. This could help mills in India, like their peers in Brazil, alternate between sugar and alcohol based on relative realizations and the economics of blending.

#3 Soft loans for ethanol capacity expansion by sugar mills, with interest subvention for 5 years including a moratorium of 1 year provided the facility supplies a minimum of 75% of its output to oil marketing companies (OMCs) for blending.

#4 Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) Programme targeting to achieve 20% blending of bio fuel with fossil fuel by 2030, now revised to 2023 (launch of E20 in phases from April 2023 onwards to enable action by all stakeholders to achieve E20 blending by 2025), with the added benefits of reducing import dependence, working towards energy security, addressing environmental concerns and providing a boost to the agricultural sector among others. The EBP programme applies to the whole of India except Andaman and Nicobar and Lakshadweep and some of the measures to facilitate its implementation are:

- Ex-mill price of ethanol fixed based on raw material used with a higher rate for ethanol from cane juice and B-Heavy molasses than ethanol produced from the conventional C-heavy molasses route. (C-Heavy Rs. 45.69/litre; B-Heavy Rs. 57.61/litre; Cane juice Rs. 62.65/litre)

- Reduction of GST on ethanol meant for EBP from 18% to 5% and facilitating the movement of ethanol

Formulation of ethanol procurement policy under which beneficial terms have been offered to suppliers such as reduction in security deposit, reduction on penalty on non-supplied quantity, and payment of GST and agreed transportation charges to the suppliers.

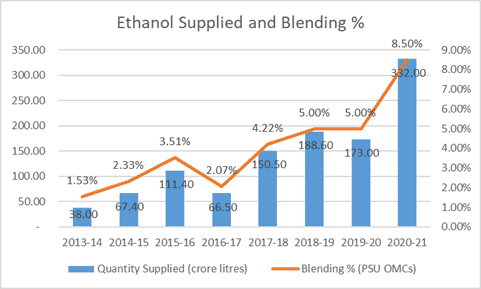

With all these policy props, ethanol supplied under the EBP programme has gone from 38 crore litres in 2013-14 to a whopping 332 crore litres in 2020-21 leading to a blending rate of 8.5%. With the 20% blending target being advanced, ethanol blending is likely to take up more of excess sugar supplies in future.

In 2019-20, ethanol producing capacity with molasses-based distilleries attached to sugar mills stood at 426 crore litres representing a target capacity of 362 crore litres at 85% capacity operation (set by Department of Food and Public Distribution). The ethanol required to meet the 20% blending rate is expected to be met from sugar as well as grains. It is estimated that in order to achieve the 20% blending, India will need an ethanol capacity of 1,000 crore litres.

- It is expected that 39 more projects (sugar mills augmenting or creating distillery capacity) are likely to be completed by March 2022 with a capacity of 93 crore litres.

- 238 projects under interest subvention scheme for capacity enhancement have been approved in September 2020 which will likely add 400 crore litres to the capacity by 2024.

- DFPD has also notified an interest subvention scheme in January 2021 for setting up / expansion of existing grain based distilleries for producing 1G ethanol which could translate into a capacity expansion of 500 crore litres.

- OMCs too are planning to set up 10-15 new grain based distilleries.

There’s no doubt that the take-off of ethanol blending can trigger a structural shift in the sugar sector in terms of diversion of cane and the ability to move flexibly between sugar and ethanol. This can smooth out the excessive cyclicality caused by glut years in the sugar cycle. But the ethanol blending programme is no panacea for the sector. There could be several roadblocks to the take-off of blending in the Indian context, which suggests that euphoria about it could prove premature for investors.

11 thoughts on “Sugar industry: Will ethanol blending prove a turning point?”

Dear Madam,

What is exit method to be followed if we are sitting at good profit. Can you please through some articles on controlling emotions and exit methodology ideally need for long term investor & short term.

Hello Sir,

Please have a look at our earlier article https://www.primeinvestor.in/five-ways-to-book-profits-on-your-stock-portfolio/

Hope this helps.

Lovely article, very insightful. Thank you.

Thank you! Glad you found it useful.

Great research but conclusion could have been better with some actionable insights.

so I am not sure what are you concluding and whats your POV on this subject. whats the advise you are giving to investors on sugar stocks? This article is just a reproduction of facts that came in news papers . But it has no analysis .specially we are looking for your view on investing in sugar stocks.

Hello Sir, Our work is split into analytical articles and insights and recommendations. We have investors who simply want ‘action’ alone and many others who don’t want such spoonfeeding and like to do their own homework provided we provide some analysis or insights besides tools (whichw e have). We cater to both. When we try to come up with insights on a very complex sector like sugar it is to cater to the second category of investors. If you find all this in the newspaper (which is not the case if you read the depth of this), then kindly look out only for our stock recommendations. The current ones are in the Prime stocks section.thanks, Vidya

Excellent overview of the sugar industry. Thank you

Thank you.

Very detailed article giving insight into sugar industry.

I think a title is missing above “#1 Controlled pricing”. The earlier section talks about “The pluses of ethanol blending”, the one below this talks about challenges/concerns/negatives, so an appropriate title would be helpful to differentiate both areas.

Thank you Sir. Point noted.

Comments are closed.